Decision making and prescribing

In a frank and open environment you can discuss the options for treatment with the aim that you help the patient - the therapeutic objective of the consultation. Not all patients have a life changing or an enduring problem that requires intervention and to do nothing might be the most beneficial therapeutic option. Watchful waiting, self-help strategies and perhaps OTC remedies can often be the most appropriate way forward. If the patient chooses a watchful waiting approach you should emphasise that you suspect their condition will settle over time but if additional signs and symptoms emerge your original diagnosis may need revising. Failure to communicate this can result in the patient thinking you have made an incorrect diagnosis.

If doing nothing is not an option and prescribing a drug treatment is the most appropriate therapeutic choice then you need to consider the clinical purpose of prescribing. This is six fold:

1. Curative

2. Symptomatic relief (also palliate)

3. Disease modifying

4. Empirical

5. Tactical

6. Preventative / prophylactic

Exploring the clinical purposes of prescribing

Think about the six areas above and which drugs might achieve these clinical purposes. Two examples are given below; list one more example for each and then consider how you might explain the clinical purpose of the medication you are about to prescribe.

| Curative example: | Malathion lotion for scabies Topical antibiotic drops for infective conjunctivitis |

|---|---|

| Symptomatic relief example: | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as Ibuprofen for joint pain A proton pump inhibitor such as lansoprazole for dyspepsia |

| Disease modifying example: | Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis Beta interferon and Glatiramer Acetate for multiple sclerosis |

| Empirical example: | Antibiotics when symptoms are highly suggestive of a diagnosis:- frequency, urgency on micturition is probably a urinary tract infection Increasing sputum production and shortness of breath in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is likely an exacerbation and requires antibiotic and oral steroid treatment |

| Tactical example: | To gain time when collecting information such as a trial of B2 agonist in a child with persistent nocturnal cough A trial of a proton pump inhibitor in an adult with persistent cough |

| Preventative (prophylaxis) example: | Inhaled corticosteroid in a patient with asthma A statin in diabetic patients with normal cholesterol (Fraser, 1999) |

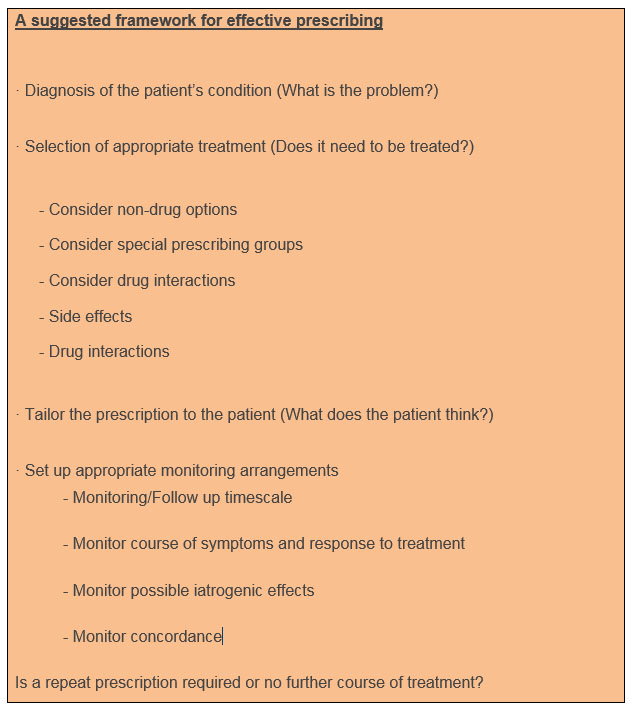

Once the therapeutic purpose of prescribing is clear to you then selecting a suitable (evidenced based) drug that meets the patient’s profile (diagnosis, current and past medication, previous adverse drug reactions/allergy and past medical history) is usually straightforward. In the hospital setting you will be expected to prescribe within the formulary set by the Medicines Committee/Drug and Therapeutics Committees. In general practice there should be a practice formulary for you to refer to, however take care as evidence is changing at a rapid rate and you need a reliable regularly updated source such as patient.info to refer to. This is a peer reviewed online resource for both health professionals and patients and you can direct the patient to this site or print off the patient information leaflet regarding both their condition and treatment. Having selected the most suitable first line evidence based drug for the patient, information about the drug should be provided in digestible portions with regular clarification of understanding; often referred to as ‘chunking and checking’. (UKCCC, 2006).

Conveying that medication is often only one part of the solution is important. Starting with small chunking of information and checking frequently for understanding helps you gauge the size of chunking needed later; how much information a patient wants or can take in varies and changes over time. However, there are a number of things that should always be explained at the time of the first prescription.

Having conveyed that there is not always a cure or ‘quick fix’ you also need to discuss the possibility that the first line drug treatment chosen may not be the right one. Advice giving should include:

1. the dosage and frequency regime;

2. the duration of treatment

3. possible side effects

There are a number of techniques which will aid you in explaining medical aims, discussing the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed medicines, and checking understanding. The main objective is to help the patient to accurately recall information later when deliberating what has happened and make decisions which are based on correct information and their subjective and lived experiences. Patient recall is enhanced and increased by signposting, explicit categorisation, repetition and the use of diagrams. (NICE 2009). The information gathering methods of summarisation and clarification/screening are continued throughout this phase also.

Give practical advice that can be followed and discuss how a structure can help by pinning the taking of medication with specific points in the day: “take this four times a day, before breakfast, lunch, evening meal and before bed” not “take this four times per day”. Be specific about important information: “take this with a full glass of water” not “take plenty of water”. Patients tend to remember instructions if they know why; “take this with food as it can cause stomach pain if you take it on an empty stomach” not “don’t take this on an empty stomach”. Use patient information leaflets as you talk through the plans with the patient and highlight or underline important parts as you progress through each category.

Please consult your eBNF in the Dr Companion app for guidance on prescribing. Remember only prescribe when necessary and always consider alternative options as well as stopping medication when it’s no longer needed.

Copyright eBook 2019, University of Leeds, Leeds Institute of Medical Education.