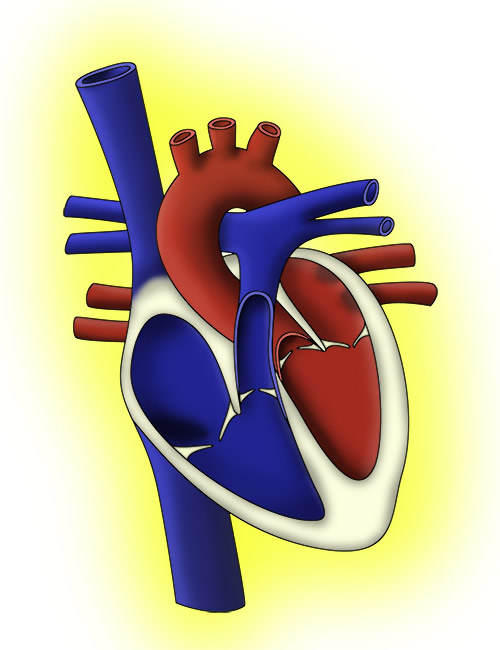

After the delivery of effective rescue breaths the rescuer should address the patient’s circulation. Effective ventilation of the lungs is pointless without adequate blood flow; first, to lungs to oxygenate the blood, and then to perfuse vital organs.

An adequate circulation can be assumed if there are signs of life, such as breathing and spontaneous movements. Should the patient have responded to the rescuers breaths (above) with a cough or gag then this would also constitute signs of life. There may be no signs of life but still an adequate circulation and this should be then assessed by palpating a central pulse. This process should take no longer than 10 seconds, and once an absence of signs of life and an absence of a pulse established, chest compressions should be performed.

Palpating central pulseChildren = carotid or femoralInfants (<1 year) = brachial or femoral. |

The central pulse of choice is different in children of different ages. In children, the carotid pulse is usually used, although the femoral pulse is also an option. Infants (i.e. <1 year) have short necks and so the carotid is not palpated. Instead, the brachial or femoral pulses are used.

A pulse may be present, but be of such a slow rate that perfusion is compromised. Therefore a rate of less than 60bpm with evidence of poor perfusion should be treated the same as no pulse at all, and chest compressions should be commenced.

Understandably, chest compressions are sometimes seen as brutal or violent. It is immensely important to give good compressions. It is unlikely that giving chest compressions to someone who doesn’t actually need them will cause them any harm, therefore do not fear giving chest compressions. The child is already in an extremely grave state, and the risk of causing trauma to ribs and soft tissues is worth taking if it can safe their life. Compressions that are too gentle or slow will worsen the child’s outcome; these have been described as “hard and fast”.

Chest compression rate is 100–120 min

Effective chest compressions can keep a victim’s vital organs perfused while help arrives. The compressions need to be of good quality to optimise potential patient outcomes, so learning the technique is immensely important.

Much like the management of the airway differs slightly, in order to accommodate physiological differences between infants and children, chest compressions are also delivered differently to different ages.

Regardless of the age of the child, the following apply:

Infants – the ideal technique involves encircling the infant’s chest with the thumbs and fingers. The thumbs are placed over the lower sternum and the chest compressed at least 1/3 of the depth of the chest (figure 5). As can be appreciated, this technique requires two rescuers: one to give the compressions and another to maintain the airway and deliver breaths. Should there only be one rescuer the compressions should be delivered with two fingers, while the other hand maintains airway patency (see figures).

https://youtu.be/dV9Z7GSARxI).

Children – the heel of the hand should be placed over the lower sternum. The rescuer should be above the patient and their arm straight (figure 7). Note how the fingers are outstretched to prevent damage to ribs. Older children, such as adolescents, may be of a sufficient size that two hands, interlocking, are needed, as in adult BLS (figure 8).

CPR RATIO = 15:2 (compressions: breaths) |

Another difference between paediatric BLS and the adult version is ratio of chest compressions to breaths. Once again there is more emphasis on rescue breaths in paediatric BLS, with a ratio of 15 chest compressions to 2 breaths. Once a fixed airway has been established (e.g. endotracheal tube) then breaths and compressions can be given continuously

If there are two or more rescuers then roles and responsibilities can be delegated. This could include sending one team member to call for help. One rescuer can maintain airway and give breaths whilst the second gives compressions. If there are more rescuers then often a single person will maintain the airway and mask position with a jaw thrust whilst a second rescuer gives breaths via a bag device. The third rescuer then gives compressions. As the team gets larger more roles are delegated such as gaining intravenous access, attaching monitoring, giving medications, sitting with the family etc.