Video: SBAR, Breathing (Nurse)

S

Hello it’s Sue here, one of the paediatric nurses on our acute admission unit. Is that the junior doctor (FY1)? I’d like you to see an 8-year-old girl called Bella Carmichael who has just attended with shortness of breath.

B

Bella is 8-years-old and is known to have a background of asthma. She has previously presented a couple of times with exacerbation of asthma and has required several admissions in the past with episodes of acute wheeze.

A

I’m worried about Bella because she is struggling to catch her breath and I don’t feel she can wait to be seen by the senior doctors who are currently in the A&E resuscitation department with another sick child. I’ve done a set of observations and Bella has a respiratory rate of 38rpm and saturations of 90% in air. She is audibly wheezy. She has a very raised Paediatric Advanced Warning Score.

R

I’d like you to see her as a priority please. Is there anything you’d like me to do whilst you are on your way?

Q – What would you like the nurse to do (RESPONSE) whilst you are on route?

On your arrival back to A&E, you start to assess the patient using the ABCDE approach.

As you approach you notice that Bella is speaking but cannot complete her sentences in one breath.

Q – Recognition: How will you assess if the airway is patent

You assess airway patency by:

• looking for chest and/or abdominal movement,

• listening for breath sounds and

• feeling for expired air.

In this case you can quickly establish that the airway is patent as the patient is speaking. However her respiratory capacity may be impaired, as she cannot complete a full sentence.

Q – Respond: how do you respond?

You feel satisfied that her airway does not require an adjunct at this point and there are no signs of airway obstruction so you therefore move on to breathing.

Q – Recognition: How will you assess her breathing?

Click here to see your clinical findings

The nurse informs you that her saturations were 90% in air, but are now 97% with 5mg nebulised salbutamol running in 8L/min of oxygen. (Note, higher flows of oxygen may be used but more of the nebulised drug will be lost from the face-mask so 6-8L of oxygen is recommended). Bella is tachypnoeic with a respiratory rate of 38pm. She has moderate chest recessions. On auscultation she has bilateral wheeze and reduced air entry bi-basally.

Q - At this point what is your most likely diagnoses, and why?

Severe exacerbation of asthma.

This child is known to suffer from asthma exacerbations and she has attended sounding wheezy with increased respiratory rate and reduced oxygen saturations. Therefore it would be sensible to treat this as if it is an asthma exacerbation, and consider reviewing your diagnosis if she does not respond well to treatment or other symptoms/clinical findings present themselves.

Q – How would you differentiate between severe and life-threatening asthma?

Acute severe asthma is defined as having any of the following features:

• Being unable to talk (complete sentences) or feed due to shortness of breath

• Saturations of < 92%

• Respiratory rate > 30/min if > 5 years or > 50/min in 2-5 years

• Pulse rate > 120 beats/min if > 5 years or > 130 beats/min in 2-5 years

• Peak flow of 33 – 50% of best or predicted

Life threatening is defined as the above with any one of the following features:

• Silent chest

• Cyanosis

• Poor respiratory effort

• Hypotension

• Exhaustion

• Confusion

• Peak flow < 33% best or predicted

Q – Respond: how do you respond?

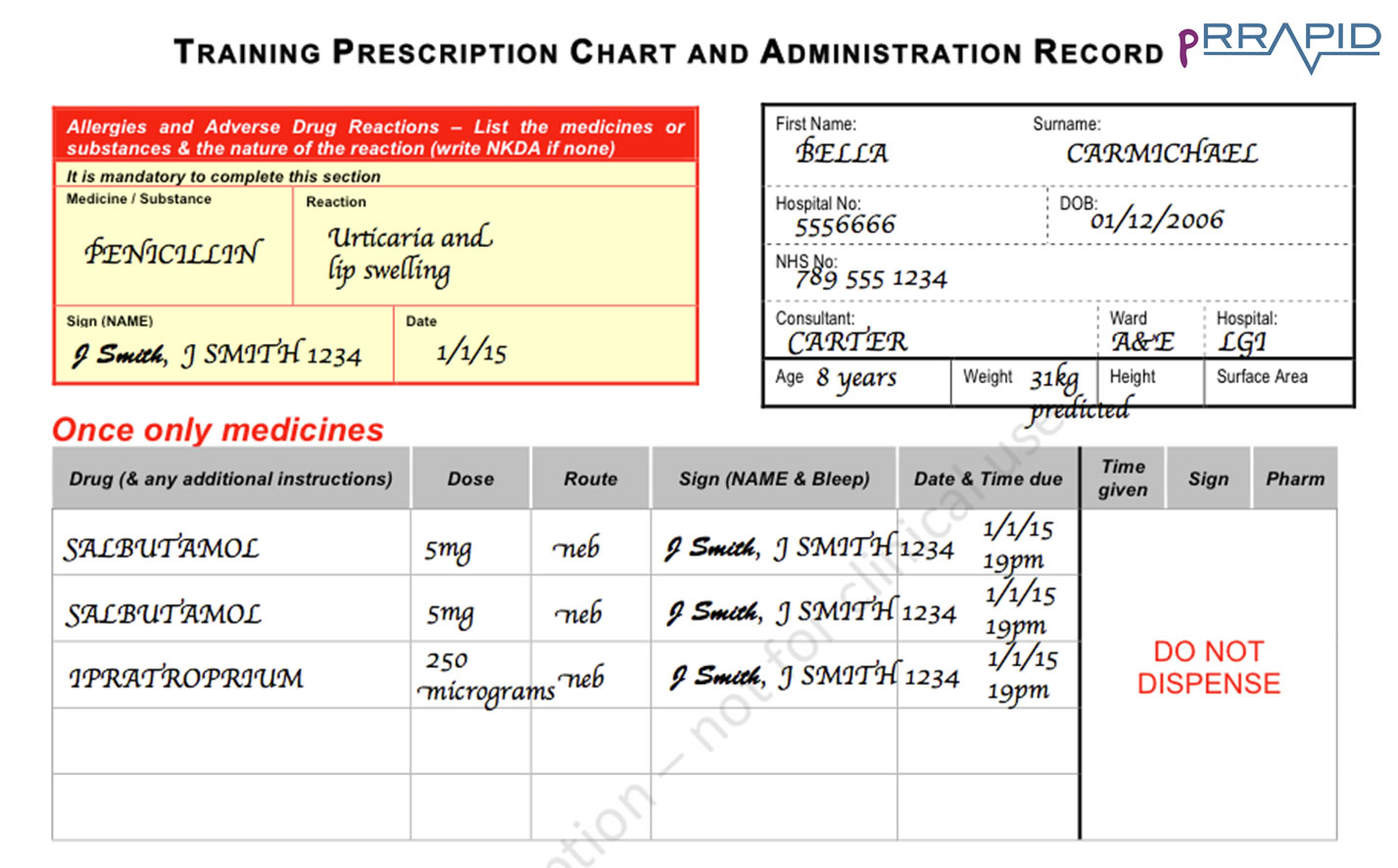

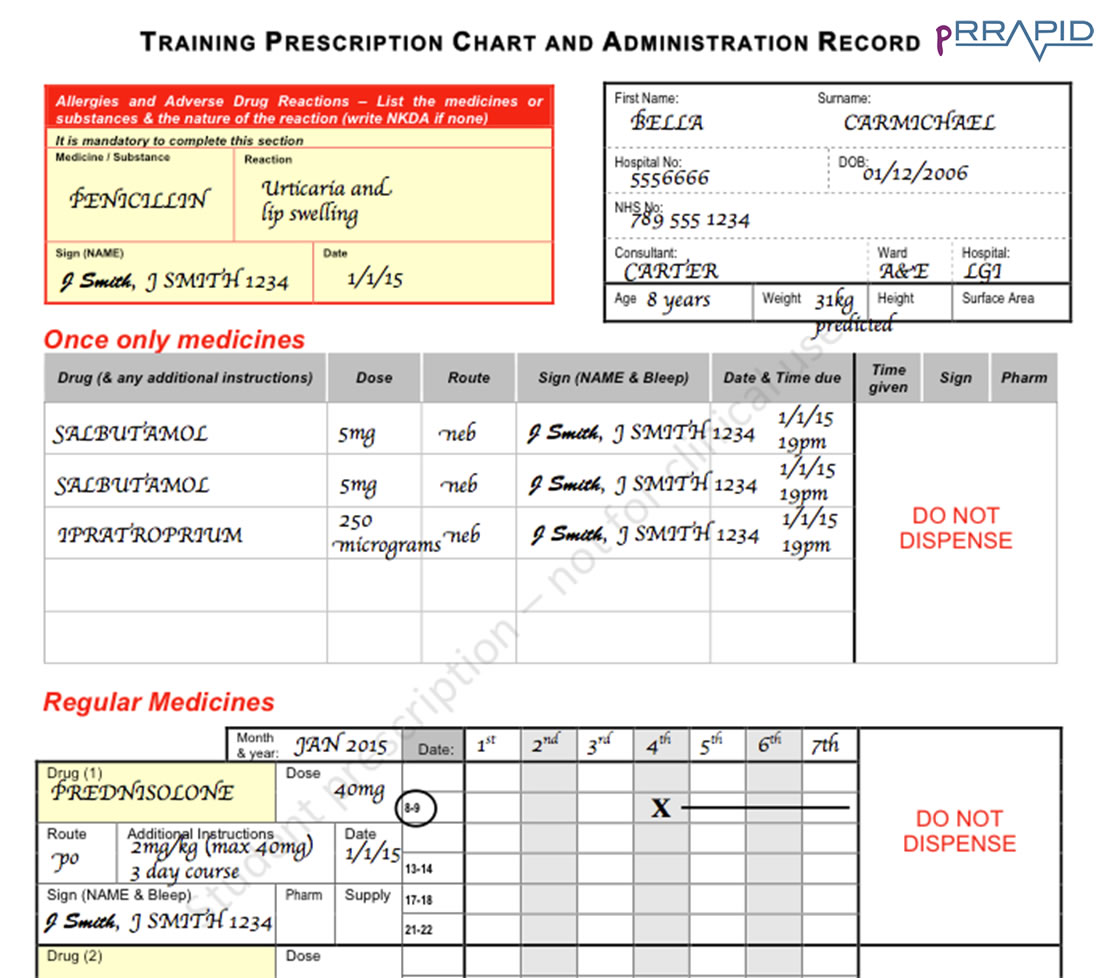

Q - Please prescribe Bella a further salbutamol nebulizer and an ipratropium nebulizer. (Click here for information on where to find the correct medication dose)

Throughout the e-book you will be asked to undertake a series of prescribing exercises on both drug charts and fluid charts. More information is included in the Prescribing Chapter. You can perform these on the drug chart that is used in your local hospital on our RRAPID drug and fluid charts. These have been designed specially for this e-book and should not be used for clinical work.

Download Drug chart

Download Fluid chart

It is important to put at least a predicted weight on the chart, even if you are not initially prescribing a weight dependent medication.

0 – 12 months: Weight (in kg) = (0.5 x age in months) + 4

1 – 5 years: Weight (in kg) = (2 x age in years) + 8

6 – 12 years: Weight (in kg) = (3 x age in years) + 7

Bella is 8 years-of-age, therefore:

Predicted weight = (3 x 8) + 7 = 31 kilograms.

A predicted weight of 31kg should be put on the drug chart. Her weight should be checked as soon as she is well enough to be weighed.

Bella has an allergy and this is an essential piece of information even if you are not prescribing a penicillin-based drug.

Bella is in oxygen and therefore can’t be treated with a large-volume spacer. You therefore must prescribe an oxygen-driven nebuliser.

Initially nebulisers are usually written onto the “once only medicines” section of the prescription chart whilst you assess response and determine how often the patient requires a nebulised medication. Once this has been established then it is better to practice to prescribe the nebulisers on the “regular medicines” section of the drug chart to ensure that it is given regularly. At times they are written on the PRN section so that the frequency can be altered depending on response, though this does risk the patient missing doses inadvertently.

Q – Acute asthma exacerbations require prednisolone. Please prescribe this

A standard course of oral prednisolone would be for 3 days at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg. A sensible approach is to therefore to give the maximum dose within this which would be 40mg. based on the predicted weight of 31kg. Regardless of weight, doses should never exceed 40mg orally for asthma exacerbation. If the patient was vomiting and unable to tolerate the oral medication then intravenous hydrocortisone should be given.

A cross and line through have been used to show when the 3 doses should be given.

Whilst the nurse administers this medication, you move onto assess circulation.

Q – Recognition: How will you assess her circulation?

You assess circulation

She is tachycardic with a heart rate of 140. The pulse volume is normal. Her blood pressure is 100mmHg systolic. Her peripheries are warm. She has a central CRT of 2 seconds, and she is alert.

Q – Respond: how do you respond?

You feel that her circulation is stable at present and attribute the tachycardia to the asthma exacerbation. Tachycardia > 120 beats/min if > 5 years or > 130 beats/min in 2-5 years is a sign of severe asthma. The tachycardia is also likely to worsen as a side effect of the salbutamol that has been given.

You ask the nurse to attach a cardiac monitor for continuous three lead tracing which is important in patients that are likely to receive lots of salbutamol. This is important for monitoring but also because salbutamol causes hypokalaemia, which can lead to cardiac arrhythmias.

Her second salbutamol and ipratropium bromide nebulisers are now running, and the nurse tells you she has given her the oral prednisolone. You move on to assessing disability.

Q – Recognition: How will you assess disability?

Click here to see your clinical findings

You perform an AVPU assessment and recognise that she is alert and speaking to her mother. Her pupils are equal and reactive to light. Her posture is normal and her capillary blood glucose is 5.8mmol/l. It is always important to check blood glucose, and is most definitely relevant in people who present with breathing difficultly. This is because diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) may present as shortness of breath as a result of Kussmaul breathing (deep and laboured breathing associated with severe metabolic acidosis). In this case, however, you are reassured to note that her blood glucose is normal, and the presence of notable wheeze on the chest makes DKA unlikely.

Q – Respond: how do you respond?

You are happy that her disability is stable and move on to exposure.

Q – Recognition: How will you assess “exposure”?

Click here to see your clinical findings

You expose Bella and find no further clinical signs. Her temperature is 36.5o Celsius.

You take a history from her mother who reports that Bella’s breathing has worsened since this morning when she helped her father plant some flowers in the garden. There have been no previous paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admissions, but says she has required nebulisers in the past for her breathing.

Bella was diagnosed with asthma 4 years ago by her GP. She has not had an exacerbation for several months. She tells you that she has a blue inhaler, which she only uses when she’s “poorly” as well as a brown inhaler. However mum admits that she stopped taking the brown inhaler two months ago as she “seemed not to need it”.

When Bella is well (i.e. no intercurrent upper-respiratory tract infection) she does cough chronically at night and will occasionally have some wheeze on exercise. Both her parents smoke and they have noticed that this triggers coughing in Bella.

Q – Respond: What does this history tell you?

First exacerbations of asthma can be life-threatening, however it is more likely to be life-threatening if there has been previous PICU or HDU admissions. You are reassured that she has never required a PICU admission in the past. Note that stopping her brown (steroid) “preventer” inhaler may have contributed to this admission. The symptoms having started after she was planting flowers in the garden suggests pollen may be a trigger for her asthma.

Her nocturnal cough and exercise induced wheeze certainly suggest chronic asthma features and therefore when Bella has recovered she should be restarted on a preventative medication such as an inhaled steroid.

Q – Now that you have assessed her ABCDE how do you respond?

You sensibly decide that since you’ve made an intervention (the nebulisers and steroids), you should reassess, starting again with A.

Q – Recognition: Click below to see your clinical findings

Bella seems to be finding it hard to speak, but you can still see chest movement and hear breath sounds.

Q – Respond: how do you respond?

You feel that her airway remains patent, and no further adjuncts are required at present.

Q – Recognition: Click below to see your clinical findings

The nurse informs you that her saturations seem to be dropping to 94% despite having now started the third mixed nebuliser of salbutamol and ipratropium bromide running with oxygen at a flow of 8l/min. She seems to becoming more tachypnoeic with a respiratory rate of 48rpm. She remains wheezy bilaterally but her air entry has reduced.

Q – Respond: how do you respond?

• You are concerned that she is deteriorating

• You ask the nursing staff to continue to give back-to-back 5mg salbutamol nebulisers along with a further dose of nebulised ipratropium.

• You want to perform a blood gas (BG). As she is a child you choose not to perform an arterial blood gas. You decide you are going to take a venous blood gas when you insert a venous cannula, which you feel you will need due to her deterioration.

• You ask one of your team to order a portable chest x-ray to rule out any other pathology that could be worsening her symptoms (pneumothorax or pneumonia) and to also bleep your registrar as you rightly feel you need some senior help.

You obtain IV access and take a venous gas with lactate, as well as laboratory blood tests for full blood count (FBC) and urea & electrolytes (U&E). Just as you obtain access and are awaiting your gas to process, your registrar rings you back.

You inform her of the patient’s condition using an SBARR structure.

Video: SBARR, Breathing (Doctor)

S

Hello it’s Omair here the paediatric junior doctor. Is that the paediatric registrar? I’ve just seen an 8-year old girl called Bella Carmichael on the paediatric assessment unit who presented with shortness of breath and I’d like you to review as soon as possible please.

B

Bella is a known to have asthma. She has previously been admitted with episodes of acute exacerbation but has never been admitted to the Paediatric Intensive Care unit (PICU). She stopped using her steroid inhaler two months ago but has ongoing intercurrent symptoms. She has become increasingly short of breath since helping her father with the gardening this morning.

A

I’ve assessed her. She was initially maintaining saturations of 97% with nebulised salbutamol. She had a respiratory rate of 38rpm but this has since worsened to 48rpm despite now being onto her third salbutamol nebuliser. She is now only saturating at 94% on 8l/min of oxygen which is driving her nebuliser. On auscultation she has bilateral wheeze and her air entry seems to have worsened. She has a pulse rate of 140bpm but her cardiovascular system is otherwise stable and her cardiac monitor shows nothing abnormal. She remains alert and orientated.

R

I have given her three salbutamol nebulisers and two ipratropium bromide nebulisers along with a dose of oral prednisolone. I think that she is deteriorating as her work of breathing has increased and her air entry has worsened. I have just inserted a cannula and taken bloods including a venous blood gas, which I’m awaiting the result of. I have also requested a portable chest x-ray. I think she has a severe exacerbation of asthma but I’m concerned that she is not responding to treatment and was hoping you would be able to review her. I will continue to review the patient regularly whilst I wait for you. If she doesn’t respond to this nebuliser we will start preparing an infusion of salbutamol and aminophylline to be given intravenously with some intravenous hydrocortisone (even if she has had her oral prednisolone). Is there anything you’d like us to do whilst we wait for you to arrive?

R

Your senior reads back the SBAR to you. She advises you that since Bella has not responded well to the nebulisers, she agrees that Bella may need intravenous treatment. She asks you to also prescribe maintenance fluids for her with potassium replacement in order to replace the potassium displaced by the salbutamol. She tells you she will be with you in a few minutes.

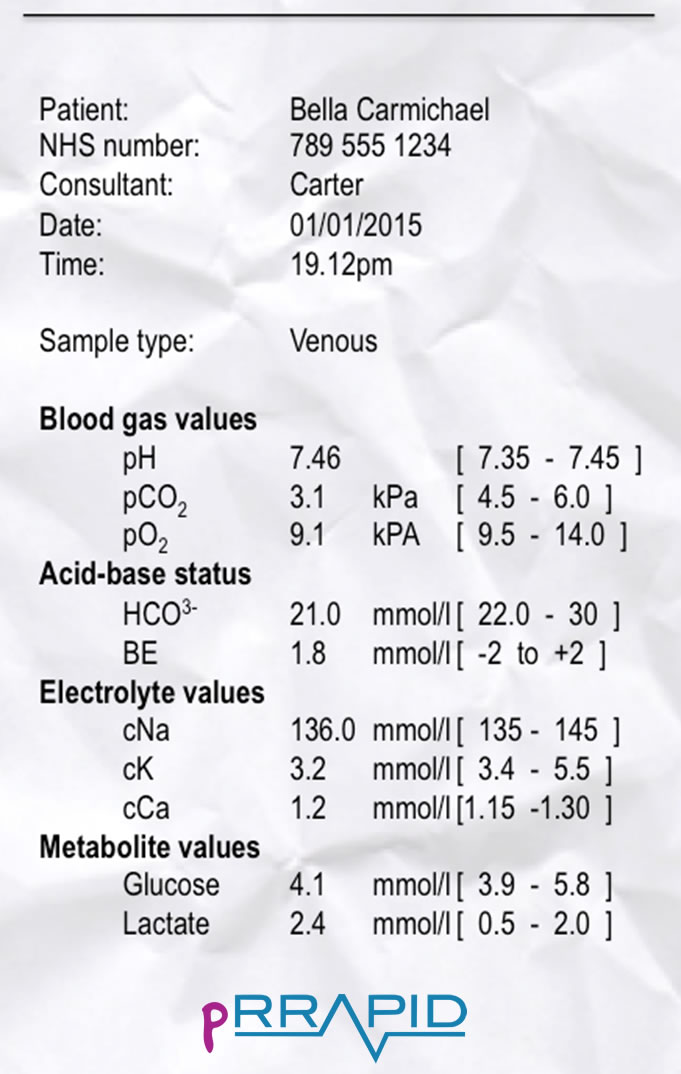

Whilst you are looking up the dose of IV salbutamol your blood gas returns:

Q – Respond: Does this concern you?

The result of the venous blood gas is partially reassuring. Bella is breathing fast (tachypnoeic) in order to maintain her oxygenation. Oxygenation is separate to ventilation which is the ability to clear carbon dioxide. This blood gas displays a respiratory alkalosis because Bella is capable of breathing off the carbon dioxide. You would be more concerned if it displayed a respiratory acidosis (i.e. low pH and raised carbon dioxide) as this would show she was tiring and not able to blow off the carbon dioxide (ventilatory failure). A raised carbon dioxide is an ominous sign of a patient who is going to collapse.

Remember the PO2 will be lower in a venous gas compared to an arterial gas. Note the low potassium, potassium should be added to her maintenance intravenous fluids.

Q – Respond: What other intravenous treatment for asthma exacerbations are there and when should they be used?

IV salbutamol, IV aminophylline or IV magnesium sulphate are the medications of choice for life threatening asthma or severe asthma not responding to initial treatment. There is no hard and fast rule, but always ensure you have senior help at hand before considering IV treatment. Many departments will require patients on intravenous therapy to be in a High Dependency Unit for such treatment.

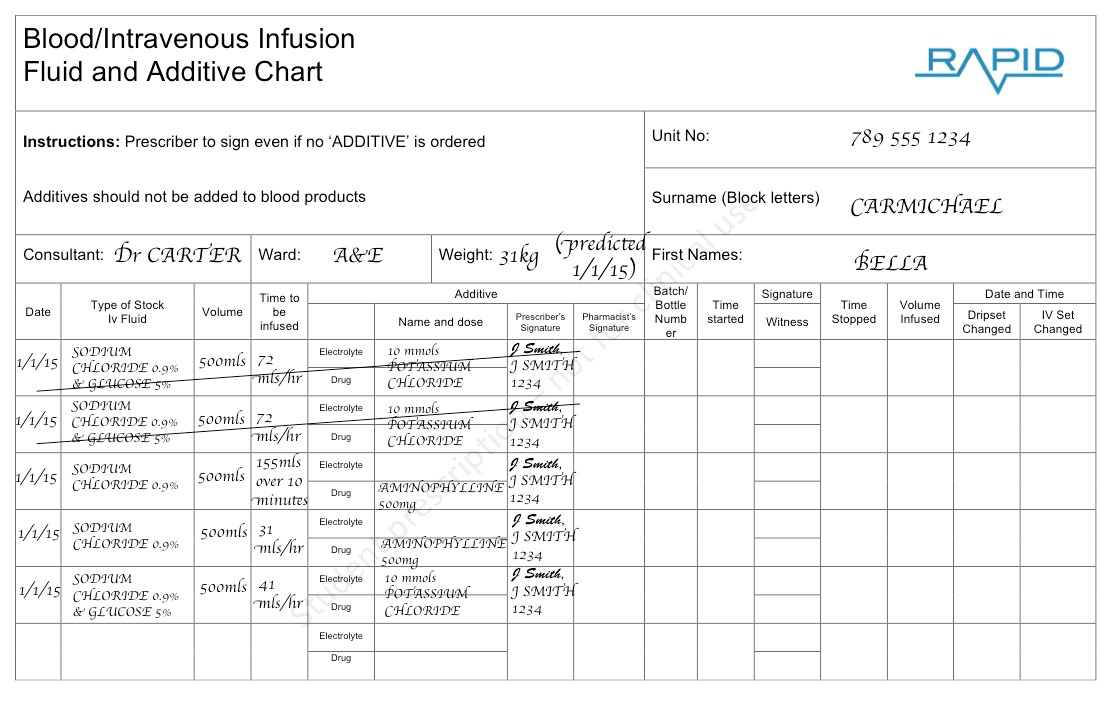

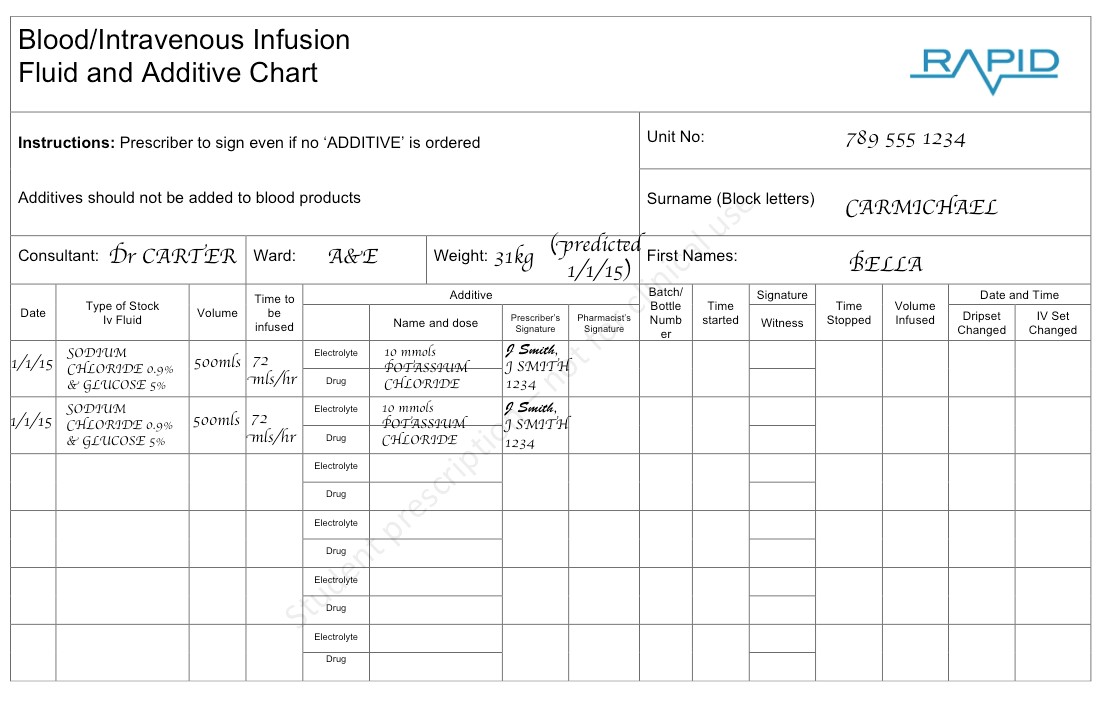

Q - Your senior recommends IV therapy and maintenance fluids. Please prescribe maintenance fluids for Bella including potassium.

Predicted weight is 31kg

Maintenance fluids

10kg x 100ml = 1000ml

10kg x 50ml = 500ml

11kg x 20ml = 220mls

Total = 1720ml (over 24hours)

= 71.7ml/hr

The hourly volume can therefore be rounded to a sensible volume of 72ml/hr.

Salbutamol drives potassium intracellularly (in fact it is used to treat hyperkalaemia in an emergency), therefore Bella’s fluids should include potassium. Children’s potassium requirements are usually 1-2mmol/Kg/Day. Therefore if prescribing fluids for a 24 hour period this should be borne in mind. In this case the predicted weight is 31kg therefore 10mmol/l of potassium chloride in each 500ml bag (20mmol/l) would meet this requirement. Electrolytes should be checked every 6 hours in children such as this, with the concentration of potassium in the fluid being altered accordingly.

As soon as possible Bella should be weighed so that the correct volume of fluid should be given.

Q – Your senior asks you to prescribe a bolus and maintenance aminophylline for Bella.

This is a difficult exercise and beyond what would be expected of a medical student. It is however a useful prescribing exercise to understand the principles of prescribing.

Three intravenous agents are commonly used in the treatment of severe asthma, namely: aminophylline, salbutamol and magnesium sulphate. In this case we are prescribing a bolus and then infusion of aminophylline.

Bella first needs a bolus of aminophylline over 20 minutes. This is at a dose of 5mg/kg (max dose 500mg). Therefore with a predicted weight of 31kg you would give 155 mg over 20 minutes. If Bella was already on a theophylline prior to admission (i.e. a regular mediation) then they would not require a bolus and would start initially on the maintenance regimen.

An infusion should then be commenced after the bolus has been given. This is started a 1mg/kg/hour. Therefore in Bella this should be given at 31mls/hr initially. This is a really difficult scenario. You’ll notice in the prescription that the original maintenance fluids of 72mls/hr now need to be crossed out and replaced by an infusion of 41mls/hr to take into account for the fluid being given for the aminophylline.