C

RESPONSE

Immediate management of the shocked patient

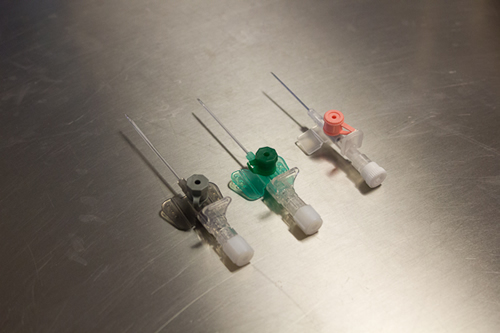

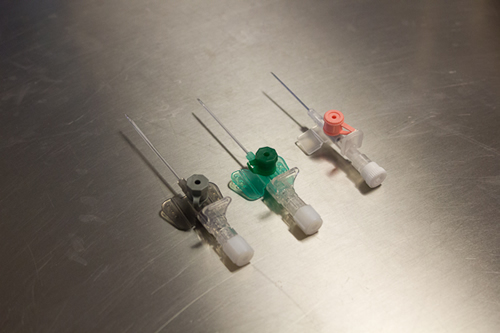

Peripheral venous cannulae. These are small flexible tubes that are placed into peripheral veins in order to administer fluids or intravenous medications. Different colours denote different sizes (pink 20 gauge, green 18 gauge and grey 16 gauge). A 'large bore' cannula refers to a grey 16 gauge or orange 14 gauge (not shown).

- Ensure airway patency

- Give oxygen 15 L/min via a reservoir mask

- Ensure adequate breathing

- Attach monitoring (oxygen saturations probe, ECG and BP)

- Intravenous access (2 large bore cannulae)

- Give a fluid challenge and assess response (cautious if evidence of cardiogenic shock)

- Treat the underlying cause

- Re-assess

Intraosseous access:

- Intraosseous access is now established as an effective route for administering drugs and fluids to adult patients. It should be considered if IV access is found to be difficult, especially in resuscitation https://www.resus.org.uk/.

This is an example of a ‘pressure bag’. Placing a bag of fluid in it and inflating the bag enables a fluid bolus to be administered quicker than if left to gravity alone or most infusion pumps.

Fluid challenge:

Rapid fluid resuscitation is essential. Administer a stat fluid bolus of 500 ml (250 mls if history of cardiac failure) of crystalloid fluid. Initially give 0.9% sodium chloride. Following review of patient consider Hartmann‘s solution, if potassium < 5.5 mmol/L and patient does not have rhabdomyolysis, oliguric acute kidney injury or DKA.

Patient response is then clinically re-assessed by monitoring their physiological variables, watching for a return to normal values (capillary refill, respiratory rate, BP, JVP, heart rate).

If the patient fails to respond or starts to develop any signs of pulmonary oedema, expert medical advice must be sought immediately and intravenous fluid administration withheld until reviewed.

If there is suspicion of cardiac disorder, for example in a patient with a recent myocardial infarction or signs of heart failure (bibasal crepitations, raised JVP, sacral/ankle oedema) then the fluid challenge should be reduced (250 ml).

Blood culture bottles

- aerobic and anaerobic.

A catheter bag and urometer to measure hourly urine output.

SEPSIS AND THE

‘SEPSIS SIX’

Sepsis is a life-threatening complication of infection. Sepsis arises when the body’s response to an infection injures its own tissues and organs. It is defined as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection”(The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA Feb 23, 2016 Volume 315 Number 8). Sepsis can affect anyone at any age. The presence of certain comorbidities and the infective pathogen can all influence the severity of the sepsis response.

Red Flag Parameters

Certain parameters have been deemed “Red Flags” for sepsis by the UK Sepsis Trust. These include:

- Respiratory rate (RR) >25/min

- Oxygen saturations (O2 Sats) <91% (not Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)

- Systolic Blood Pressure (BP) <90 mmHg

- Heart rate (HR) >130/min

- P or U on the ACVPU scale

- NEWS2 >7

- Purpuric rash

Septic Shock

Septic shock should be defined as a subset of sepsis in which particularly profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk of mortality than with sepsis alone. Patients with septic shock can be clinically identified by a vasopressor requirement to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg or greater and serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L in the absence of hypovolemia. This combination is associated with hospital mortality rates greater than 40%.

Assessing the Septic Patient

At present there are no diagnostic tests for sepsis. In the UK NICE does not provide a definition of Sepsis, it simply uses deranged observations/physiology to suggest treatment should be considered/started depending on the degree of derangement.

The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score is “a bedside prompt that may identify patients with suspected infection who are at greater risk for a poor outcome.” Clinically, organ dysfunction can be defined by an increase in the qSOFA score of 2 points or more. This is also associated with a “3- to 14-fold increase in in-hospital mortality”

|

Points for answering Yes |

Points for answering No |

Altered mental state GCS<15 |

1 |

0 |

Respiratory rate ≥22 |

1 |

0 |

Systolic Blood Pressure ≤ 100mmHg |

1 |

0 |

There are, however, 2 questions which should be asked when assessing a patient and thinking “Could this be Sepsis?”

- Do they have signs and symptoms of an infection?

- Do they have deranged physiology/observations?

If the answer to question 1 is Yes, the next step is to assess how unwell the patient is in response to the infection.

To assess how unwell the patient is in response to the infection all body systems must be reviewed and it must be considered if there are signs of an infection – temperature, pain, vomiting, cough/sputum, dysuria, rashes, erythema, pus, diarrhoea etc. Sources of infection must also be considered such as drains, intravenous access, catheters etc.

If the answer to question 2 is Yes then the next step is to assess if the deranged physiology/observations could be due to an infection or if there is another non-infective cause (pancreatitis, pulmonary embolus, gastro intestinal bleed etc.).

To assess if the deranged physiology/observations could be due to an infection the ABCDE approach should be used. Using the ABCDE approach the respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, urine output, venous blood gas for a lactate, mental state and presence of rashes should be reviewed. The observations can be grouped together to give an overall score- the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2). As the name suggests this is used nationally and is a useful common language to communicate to colleagues the level of derangement of the observations.

Most hospitals will have specific actions that need to be taken when the NEWS2 hits a certain value – for instance NEWS2 >5 – screen for sepsis or NEWS2 >7 call outreach and ensure expert review. However, it must be noted that in some cases the NEWS2 will not accurately communicate how unwell the patient is. This may occur, for example, in a patient with a pneumonia who initially has a raised respiratory rate. As they tire their respiratory rate will drop. This is not a sign of clinical improvement, it is a sign of significant deterioration, but the patients NEWS2 will have improved due to the decrease in respiratory rate. The NEWS2 may also not accurately communicate how unwell the patient is when the patient is young. Young patients are able to compensate physiologically and therefore their NEWS2 may remain within normal range despite being very unwell.

If the answer to both questions is Yes then the next step is to rapidly move to treating the sepsis.

Treating Sepsis

Consider the following case:

Mr Smith is 55 years old and previously fit and well. He has been admitted to the surgical assessment unit (SAU) from his GP practice with right upper quadrant pain, vomiting and a fever. His observations at the GP were:

- Alert

- Temp 38.5◦C

- RR 16/min

- Oxygen Sats 97% on room air (RA)

- HR 110/min

- BP 130/80 mmHg

- NEWS2 = 2

He has arrived on the ward and his observations are as follows:

- Alert

- Temp 39.5◦C

- RR 22/min

- Oxygen Sats 94% on RA

- BP 95/50 mmHg

- HR 135/min

- NEWS2 = 11

Following review of Mr Smith, he has signs and symptoms consistent with a biliary tract infection and is showing deranged physiology with Red Flags for sepsis.

Sepsis can be rapidly fatal; however, timely management can improve the prognosis for the patient. Think BUFALO/Sepsis 6

B- take Blood Cultures

U- start Urine output monitoring/check U+E/Urinalysis and urine cultures if positive

F – Start IV Fluids – Hartmann’s or 0.9%NaCl – 1 L stat.

A – Start Broad Spectrum Antibiotics

L – Check the Lactate (venous gas)

O – Apply Oxygen – 15L/min.

This should be done within 1 hour of diagnosing sepsis and following the initiation of management the patient should be reassessed to check the response. The patient must get an expert review from a member of the team, at St3 Level or above, and ideally a Consultant within the next hour.

Appropriate antibiotics must be prescribed as per Trust guidelines. The key is to “start smart” then focus the therapy more specifically once the cause becomes clearer.

Good antimicrobial stewardship is possible provided the blood cultures and other appropriate cultures (e.g. urine cultures, swabs etc.) are taken and the patient undergoes regular expert review to consider if the antibiotics are still required. All antibiotic prescriptions should be reviewed at 72 hours to see if the patient is improving sufficiently to switch to oral antibiotics – discuss with your ward pharmacist and Consultant if you are unsure. Use the acronym “ACED” – Apyrexial, Clinically improving, Eating and Drinking – if the answer to all these is yes consider switching to an oral alternative antibiotic.

For more information visit the "Surviving Sepsis" campaign online: www.survivingsepsis.org.

CARDIAC ARRHYTHMIAS

An arrhythmia is a disorder of the heart rate or heart rhythm, such as beating too fast (tachycardia), too slow (bradycardia), or irregularly.

The electrical impulse that signals your heart to contract begins in the sino-atrial (SA) node. This is your heart's natural pacemaker. The signal leaves the SA node and travels through the heart along a set electrical path. Arrhythmias are caused by problems with the heart's electrical conduction system.

Some arrhythmias can be relatively benign (e.g. rate controlled atrial fibrillation), others are immediately life threatening (e.g. ventricular tachycardia), and some may have varying effects on the patient.

Tachyarrhythmias

A tachyarrhythmia is any disturbance of the heart’s rhythm resulting in a rate greater than 100 beats/min. They can be subdivided into narrow complex tachycardias (QRS < 0.12 s) and broad complex tachycardias (QRS > 0.12 s) depending on the width of the QRS complex. Broad complex tachycardias are either ventricular in origin or supraventricular with aberrant conduction (i.e. bundle branch block). Tachyarrhythmias can also either be regular (e.g. supraventricular tachycardia) or irregular (e.g. atrial fibrillation).

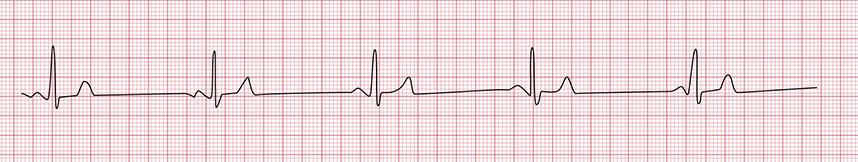

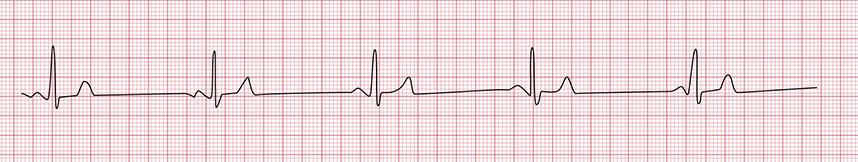

Atrial fibrillation. Note the irregular rythmn and absence of P waves.

Bradyarrhythmias

A bradyarrhythmia is an arrhythmia with a rate less than 60 beats/min.

These can be physiological (e.g. in athletes), cardiac in origin (e.g. atrioventricular block) or non-cardiac in origin (e.g. vasovagal or drug induced).

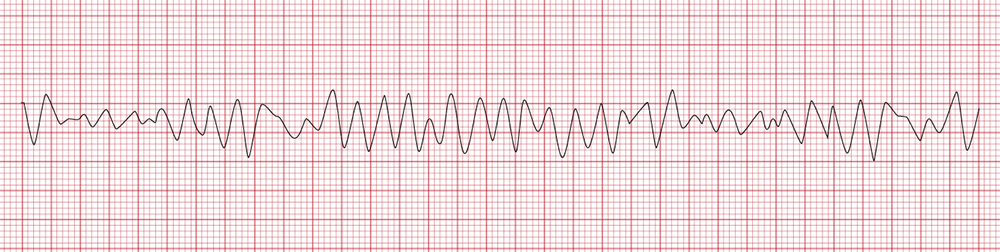

Sinus bradycardia with a rate of 37 beats/min.

Adverse features

The clinical effect of an arrhythmia depends largely on the rate but also on the type of arrhythmia (e.g. ventricular fibrillation is never associated with a significant cardiac output).

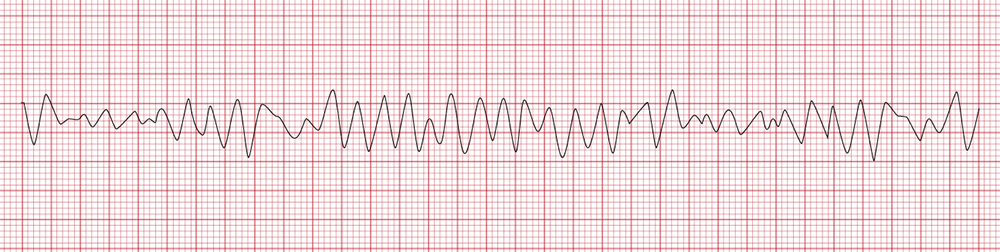

Ventricular fibrillation

The management of arrhythmias is dependent on the presence or absence of adverse features.

The following adverse features indicate the patient is unstable, due to the underlying arrhythmia, and are an indication that urgent cardioversion may be required.

- Shock

- Syncope

- Myocardia ischaemia

- Heart failure

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME (ACS)

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) is basically an umbrella term that includes:

- Unstable angina

- NSTEMI (non ST elevation myocardial infarction)

- STEMI (ST elevation myocardial infarction)

An acute coronary syndrome in the majority of cases occurs due to an acute thrombus forming in an atherosclerotic coronary artery. This obstructs the flow of blood to the myocardium causing damage to the myocardial cells. The extent of this damage determines whether it is an unstable angina attack, NSTEMI or STEMI.

Unstable angina

Pain usually felt across the centre of the chest, tightness or a heavy feeling. The pain often radiates to the throat or left arm and may be associated with nausea, sweating and shortness of breath. When the pain occurs with increasing frequency and brought on by progressively less exertion, this is termed unstable angina. The ECG may show signs of ischaemia (ST depression) but troponin levels are not raised (as this would indicate an NSTEMI).

NSTEMI

Pain similar in nature to angina but sustained (20 minutes or longer). ECG changes may show ischaemia (or be normal) but no evidence of ST elevation MI. A raised troponin level at 12 hours following the onset of the pain indicates myocardial damage and confirms the diagnosis.

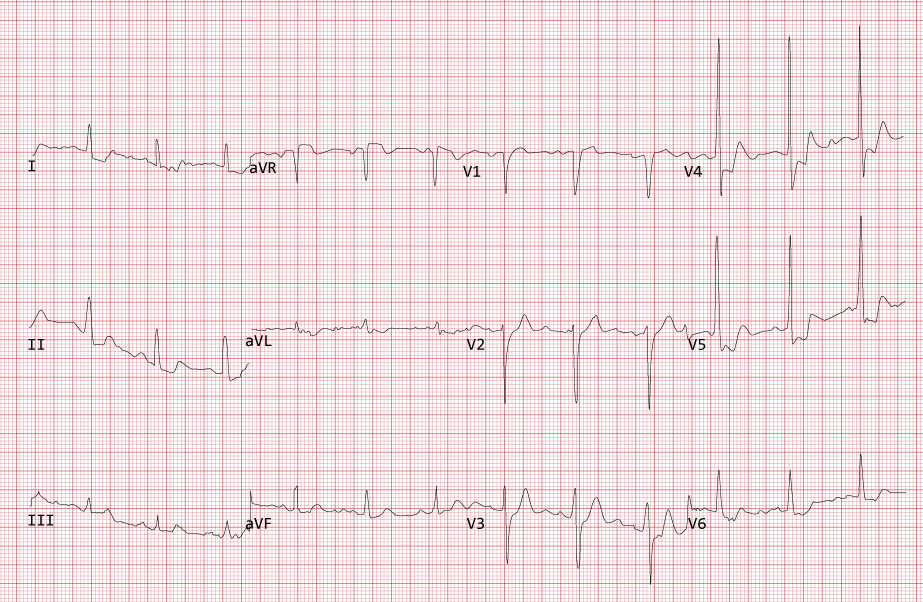

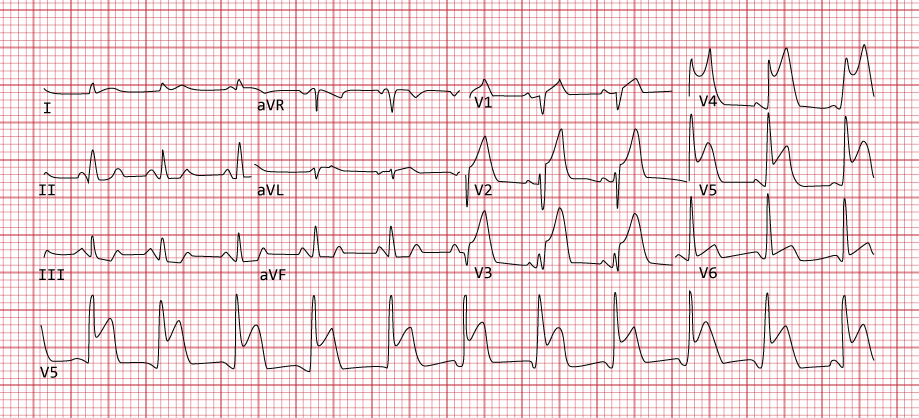

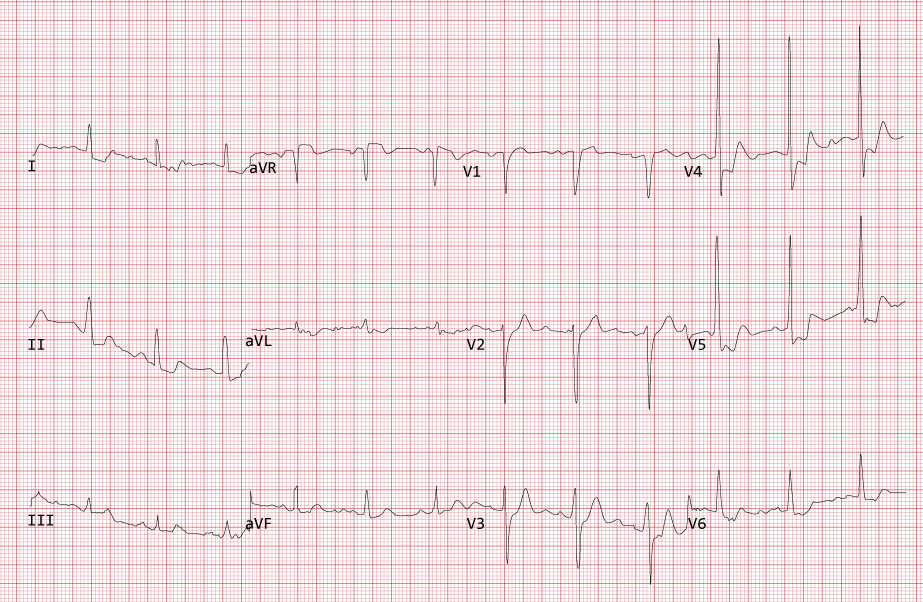

12 lead ECG showing anterolateral ischaemia. There is ST depression in leads I, II, V3 – V6. There is also evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy.

STEMI

STEMI is characterised by persistent myocardial pain, (again similar in nature to angina but more severe) with evidence of ST elevation on an ECG. Reperfusion of the offending coronary artery is required, by removing the thrombus. This is often done by a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) where a coronary angiogram locates the thrombus, and then a guidewire is passed through it enabling a balloon to be positioned at the site of the occlusion and inflated to open the artery.

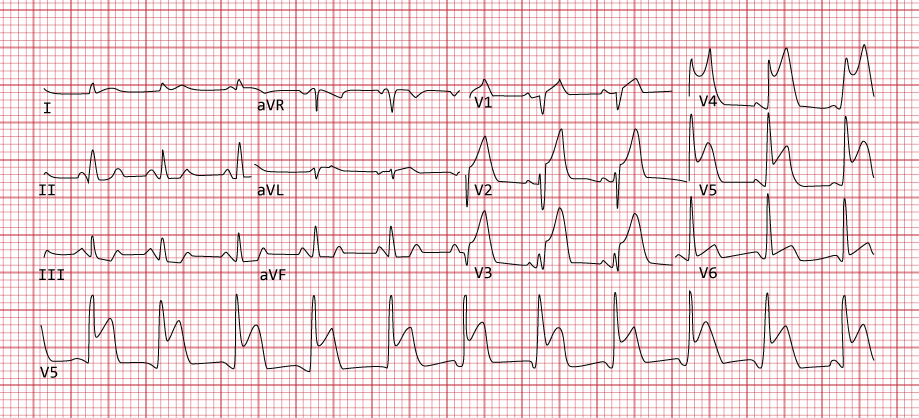

12 lead ECG showing an anterolateral ST elevation myocardial infarction.